Will Asia rise with the elephant-dragon tango?

For a brief moment, you’d think there is no comparison between the two! One is a $11.3 trillion economy, while the other is a modest $2.1 trillion upstart.

At one end stands the mystical dragon, occupying the position of the second-largest economy in the world. On the other is the resolute elephant, which is expected to become the second-largest economy globally, rising from the current sixth position.

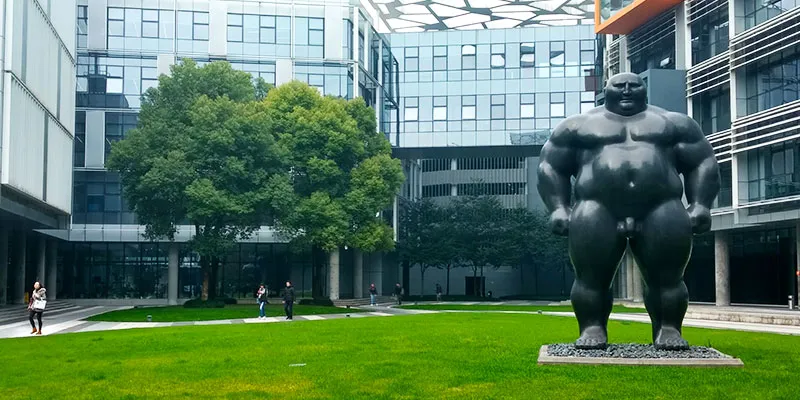

But, if you think about it, the comparison doesn’t seem irrational after all. As a bus full of Indian entrepreneurs snakes its ways through Beijing on a smoggy morning, all you can see on the faces of the passengers is sheer awe. The smog is unable to hide the scale of things in this city, from its skyscrapers to its flyovers.

Our Chinese friends inform that the city that we see now has sprung up just over the last decade. Three decades ago, the city’s face was largely dotted by four-section compounds.

What keeps striking you as you look out the window is the entirety of the scale and infrastructure that the Chinese have so quickly managed to achieve.

How big is big?

So, what is implied when we talk scale for the 1.4-billion (approx) population of China?

With more than half of the world’s building materials being used for construction in China, it is said that the number of people living in urban areas of the country has grown from 19.7 percent to 49.7 percent in 2010.

David, our guide in Beijing, points out some of the reasons for this rapid urbanisation. He says,

“This is a new China where everyone wants to migrate to bigger cities for better education and better opportunities.”

Such is the inflow to urban areas that the government is now asking students to complete their primaries in their own districts.

The netizens

According to Chinese think tank China Academy of Information and Communication Technology (CAICT), the China Internet Industry reached ¥ 1.24 trillion ($179 billion) in 2016, with close to 716 million Internet (60 percent) users or netizens in 2016. Data also shows that out of the entire base, 673 million (almost 94 percent) of these Internet users were on mobile.

From an Indian standpoint, the number doesn’t seem far behind.

According to a recent report from Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI), as well as IMRB International, the number of Internet users in India is expected to reach 450-465 million by June 2017, with the overall Internet penetration in the country standing at 31 percent.

On the supply end, according to the think tank, as of January 2017, application stores in the world accumulated more than 15 million applications around the world, of which 10 million were offered by the China market. Moreover, the number of websites registered in China is close to five million.

On the other hand, it is also no secret that the Chinese Internet market is witness to fierce competition. The rankings for the top emerging apps keep changing every now and then, and in some scenarios, competitive businesses can rush into the 'Top 50' applications by usage in just two years.

Digital payments leader AliPay, which just two years ago had a market monopoly of 90 percent in terms of usage and volumes, has now been pushed back to 50 percent by main competitor WeChat Pay, Tencent’s very own payment service.

There is a strong consensus among Chinese users on how this came about.

“We have WeChat open all the time for messaging and hence wouldn’t like to switch over to another app (AliPay here) to make payments of any kind,” a typical user says.

The learning? Convenience trumps all. What surprised me was just the fact that opening another app for using services could be a cause for such a downfall of a company.

But, I was still curious to find out how WeChat, a social messaging leader, got the better of a service designed only for payments and services, and beat them at their own game.

The answer was all around, just that I wasn’t looking close enough.

By the third day of the trip, Indian entrepreneurs seemed to have a new obsession. Our WeChat group was buzzing with red envelopes having various messages scripted on them, assigned with some yuan (Chinese RMB) to them.

The person who opens it first gets the highest fraction of the amount allotted to the envelope. At first the idea looks absurd, almost silly, but on trying it, you understand the competitive and gambling thrill of these red envelopes, which WeChat popularly refers to as 'Red Packets'.

While the fraction cut can be stipulated according to the sender, the end rush always results in people scrambling to be the first to open the envelope.

And this tying up of payments with gamification got users comfortable with the idea of using digital payments on a social messaging app. An article from Fast Company claims that during the launch in 2014, the usage of WeChat payments tripled from 30 million to almost 100 in a month. This Chinese New Year, WeChat users sent 409,000 red packets in a single second, states the article.

No wonder, on the debut of Red Packets in 2014, Alibaba founder called it the ‘Pearl Harbour moment’ for his company, rightly giving China the tag of being the 'Economy of Super Apps', where multiple services are all bundled under one platform.

However, it is safe to say that the Chinese economy is still quite cash dependent.

The Internet economy

“Par, unke paas Alibaba hai, Baidu hai, Tencent hai, tumhare paas kya hai?”

Although publicly listed in other stock exchanges, China is still the operational home to the world’s biggest Internet conglomerates namely, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent (popularly referred to as the BAT).

According to CAICT, Tencent takes its place right after the likes of Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, and Facebook, and is touted to have a market value of $206 billion, with an annual income of $16 billion. Following the lead is e-commerce group Alibaba, standing at a market valuation of $205 billion, and generating an annual income of $25 billion.

Then there is Baidu, which stands at a market valuation of $62 billion, generating an annual income of $10 billion. Others also include Xiaomi, the smartphone manufacturer, with a market valuation of $46 billion.

But what, fundamentally, sets Chinese businesses apart from the global behemoths? A spokesperson at CAICT tells me that businesses like Google, Amazon, and Uber have aspirations of going global right from their inception. While viewing global economies, firms of the West look at seizing the global market through providing standardised services, turning for large global market share.

China does the opposite; the mantra remains ‘Go Local and Build Local.’ Hence, strengthening their positioning by relying on the local market, Chinese firms rather import outer serving models for local use. For example, Alibaba uses Chinese customer’s desire to own global goods to its advantage and caters to that want actively.

Baidu-Alibaba-Tencent, the nemesis of Chinese startups?

But all that glitters is not gold.

The existence of the B-A-T nexus may not necessarily mean a positive sign for China’s emerging economy of startups.

A Chinese source that didn’t want to be named, told me,

“Tracking the market closely, Goliaths like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent can get bullish to invest or acquire newer businesses and areas, which happen to be out of their purview of expertise and portfolio. A lot of potential upcoming Chinese startups are, therefore, trying to avoid investments from the trio. Further, the B-A-T nexus continues to invest in rival businesses to shut out the others and get first-mover's advantage in a particular domain amongst other Chinese companies.”

There could be some weight to these sentiments. Let’s take the example of Didi, the ride-hailing app whose founder, Cheng Wei, was tracked in 2013, and sweet-talked into getting funding from the Shenzhen-based Goliath Tencent, according to an article by Bloomberg Technology. Cheng, at that time, was reluctant to raise funding from the behemoth.

Little was known that the ride-hailing app will end up driving global cab aggregator Uber out of the Chinese markets. And the credit went to Tencent’s then acquisition chief Richard Peng, making him one of the most sought-after deal-makers in the country.

By just a quick search on Crunchbase, the number of acquisitions by the B-A-T nexus stands at 15 since 2015, with Alibaba closing in seven, Tencent with five and Baidu inching in three acquisitions.

But startups in China are having reduced focus in the area. Take, for example, APUS, which claims to have one billion acquired users worldwide. The tech firm has only 50 million Chinese users. On asking an employee about reasons for this reduced focus on China, pat comes the reply, “We don’t want to be a part of the B-A-T.”

Why is China running global?

But it would be rather unfair to push the blame on the behemoths for smaller player’s global strategy, especially when their existence is actually fostering the entire ecosystem.

There is no secret about the success of Chinese companies in markets like India. Consumer electronics company Xiaomi claims to be now the second largest smartphone manufacturer for India, having sold close to 1.36 million devices in India during Diwali last year. While Android developer APUS is already pegging 20 percent of their global user base in India within just a year of launch in 2016.

So, what is causing these companies to run to global markets?

Jason Wang, Co-founder and CEO of Chinese Accelerator, ZDream Ventures, might have some pertinent answers to the question.

He says the strategy is go global or go rural.

“For Chinese firms, going global is no longer a matter of choice or want, but rather the need of the hour,” he adds.

This is because the urban markets in China are highly saturated with the inflow of various mobile Internet products and services. Hence, this leads companies to look at ecosystems that still have vast potential to grow, such as the Indian market.

A paper on ‘Trends and Predictions for China’s Tech Industry in 2017’ by China Tech Insights highlights the same, in that the China’s mobile Internet market in major cities largely lost its strong growth momentum seeing total penetration of all types of Internet innovation.

This is causing even behemoths to change winds and pivot to look at small and mid-sized Chinese cities where the mobile market is still growing with mobile Internet penetration.

“We are soon to reach a ceiling, therefore companies are figuring out newer territories to settle,” adds Jason of ZDream Ventures.

Moreover, globalisation is increasingly becoming an inevitable option for Chinese tech, even as the market is opening up to global competitors entering their turf.

But what is fuelling this confidence in a country, which historically has been closed to the world due to its major language barriers and cultural differences, and political and economic policies?

Jason helps me out there as well. He reiterates that after successful IPOs of Chinese technology companies, there is ample amount of domestic capital flow being pumped into businesses through strategic investments by the B-A-T.

Secondly, the Chinese ecosystem is a much matured one that has experimented and seen the entire lifecycle of how products work at scale. These ingredients make Chinese businesses more capable of building for emerging markets and achieving instant scale.

Jason also adds that costs might still be lower in emerging markets, which may make it lucrative for Chinese firms to operate in such markets. He cites the example of Customer-Acquisition-Cost (CAC) while adding,

The cost to acquire a customer in global markets is less when compared to China. In China, CAC can go as high as $5, owing to market saturation and conversions, while in markets like India, the cost still remains to be few cents.

For Hangzhou based giant, Alibaba, only seven percent of the group’s revenue comes from commerce outside the country. Therefore with plans of increasing their active buyer count to two billion by 2016, even the biggest technology company is forced to look outside its own playing ground.

And, now, since India is a big focus for Chinese giants, a fact proven by rigorous strategic investments by Tencent and Alibaba, what is the sentiment that Chinese investors follow for the subcontinent?

India, the destination for Chinese investments?

On my discussions with several Chinese investors and entrepreneurs, however, India didn't appear too high on the list of priorities at the moment.

Li Jian, Co-founder of ZDream Ventures, reiterates the four crucial parts to raising capital for investors: raising it , investing it, managing their portfolio, and looking at successful exits.

While the first two aren’t much of an issue, the latter two are particularly difficult for Chinese investors in a market like India. He remarks,

“Venture capitalists in China don’t have local teams in India to manage their portfolio, while none of the big Internet commerce companies in India have been able to give a successful exit, which could be a matter of worry for them,” he adds.

Zijing Zhou, Founder and CEO, Ether Capital, agrees.

“Today, the Chinese market has seen large capital and high development. And we think the same will happen with India at an even better scale. Investors in China are exploring investment opportunities in Indian businesses, but we need a local team to help us in identifying these businesses,” he says.

And that’s not about it. Jason adds,

Well, Chinese investors might think that infrastructure is a huge issue for growth in India. And consciously use that as a key factor for investments in any business. From my understanding, Chinese investors are actively evaluating the Indian market, but it might take a few more years before they actively start investing in Indian businesses. But strategics are happening.

And this, despite the big language and cultural barriers that exist between the two nations.

Min Zhang, Managing Partner at Empower Investment, opines that they are still learning about the ecosystem in India since they don’t know the market too well.

When the elephant finally tangos with the dragon?

He believes that while China is ahead in sectors like e-commerce, logistics, and payments, India has a unique advantage over China in sectors like SaaS (Software-as-a-Service), P2P, as well as software capabilities.

And this could be partially because of the back offices of global technology giants, which India is home to. But what could be India’s biggest advantage could turn into a significant handicap. Zhang says that while it’s good that India is a free market, there runs a threat of it being bulldozed over by global competitors. This is where China’s aversion for free markets and its supportive policies make it is easier for Chinese companies to build and scale their businesses.

But, China’s handicap could also be the vastness of its market, which can be difficult to usurp in one go.

But more than the differences, the way our ecosystems are built are extremely similar: Zhang says that between 1995 and 2002 there were only US dollar funds in China until the Chinese funds started showing up and built domestic capital overtime to trump the influence of Western funds.

Secondly, like large portion of the population in India, China users completely skipped the PC revolution and jumped directly to mobile. This is very unlike the West where the population went through the entire course of personal computing before moving onto mobile.

Zhang adds,

It is only now that we have our own thinking and philosophy, which allows us to find better opportunities across emerging markets. And we will see that happening in India as well, but gradually. There will be domestic capital, and high development as the Indian ecosystem matures.

To this, Jason drew a plausible scenario for the future, which remains with me throughout the trip. He says,

Capital and investments follow their own flow from matured to emerging markets. At one point of time there was capital, which came from the West to China. Now, hopefully we will see capital flowing from China to India, and later from India to other emerging ecosystems like, maybe, Africa.

However, that still doesn’t take away from the fact that Chinese businessmen, like Zhang, find infrastructural challenges, like the lack of good network infrastructure and high cost of mobile phones in India, a little worrisome.

By the end of the trip, I was at Shenzhen, and I had to cast all my learnings in the light of our very own Indian ecosystem.

I happen to speak to Karthik Reddy, Managing Partner at early-stage fund for startups Blume Ventures, who had been in several meetings with Chinese corporates and venture capitalists.

Over the course of his meetings, he believed to have understood that the Chinese investors are waiting for the clutter to clear and let the ecosystem evolve to even a sub-market level before investing.

Space and distance has clearly not brought clarity, as just like the Indian investors, Chinese investors too are equally confused about the developing India story. Karthik adds,

Even they don’t know what is going to really happen in India. So they aren’t really coming all in and are only making small strategic bets or risking some of their capital in the run.

He also adds that even for strategics there is no urgency to acquire their bets until everything is figured on the workings of the market and product. Obviously, since it is easier for these behemoths to risk capital rather than lose out on management operability.

So, what is going in favour of successful Chinese businesses, which we seem to be lacking in our ecosystem? Karthik highlights a few things, including strong government backing to build and push for robust infrastructure, higher consumption power since increased per capita GDP, and, most importantly, innovation for locals.

Karthik believes that while capital can be foreign, success of a company depends on all execution, which continues to be local dependent.

But they see a large opportunity in India, especially for infrastructure building. A large strategic which we met during the trip maintained that the Chinese behemoths are keen to help India in building their critical physical and digital infrastructure.

But what India still has to reach is the tipping point where Indian investors see success with their investments. Karthik adds,

“When investors see success in India is when they will realise what is construed as success.”

Once that cycle kicks in is only when we would be able to have capital gains to invest in developing other sectors. Further, Karthik believes that the Chinese play on a different scale altogether. He explains that profits are dependent highly on the workings of demand and supply. China has the capacity to serve owing to the titanic infrastructure and the government’s commitment to build it.

This, in turn, helps in speeding up the scaling process and you can see network effects much faster in China than in other markets. After achieving profitability, what gives the Chinese the confidence to play in emerging markets are these profits and positive cash flows.

He adds,

The risk-taking appetite is at a higher level owing to the positive cash flows. People risk gains and not principal. And it is this risk cycle puts China in a different league.

Also, Chinese businesses are implementing models, which have worked for them in other markets where they understand that infrastructure is weak and they have the necessary expertise to build it. The price value paradigm is the third factor of success to Chinese businesses.

For example, Xiaomi provides products and services at steal price in India, while ensuring the perfect confluence of design and product.

And Sanjay Nath, Managing Partner at Blume Ventures, rightly sums up the China visit saying,

Chinese are the masters of scale and speed. With clear lines of leadership and remarkable execution, they unite in ways that we may fail to understand. With very little distractions (of religion and biases) and more focus, there is much we can learn from them and not necessarily ape them.

One can only say that the dragon is lifted by the aspirations and potential of the elephant and is confident of its collaboration to fight out the West, building a truly powerful Asia-only supremacy.